A conversation with Boston Celtics' Enes Kanter

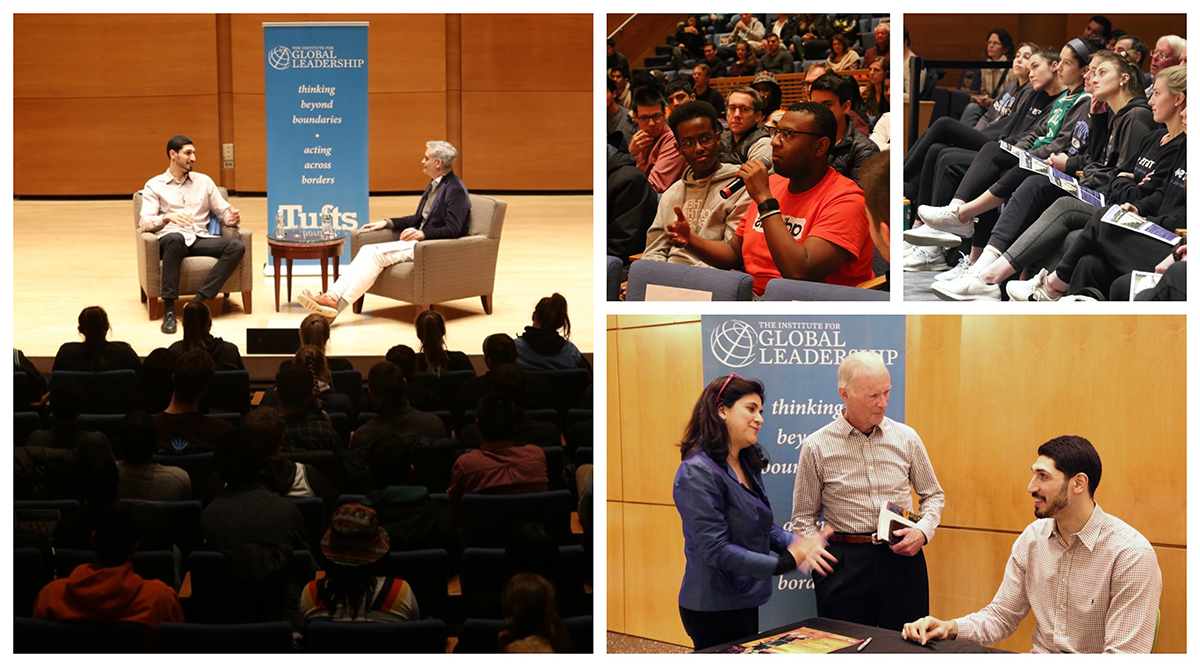

Enes Kanter, who plays center for the Boston Celtics and is an education and human rights advocate, shared his reflections on his immigration journey, playing in the NBA, and his public service with the Tufts community at the end of February. His visit was made possible by Institute for Global Leadership (IGL) Board Member, Ed DeMore, who has longstanding ties to the Turkish community.

Boston Globe Magazine Staff Writer and IGL Alumnus Neil Swidey (A’91) moderated the discussion, “A Conversation with Boston Celtics’ Enes Kanter. Tufts students and members of the local community crowded Distler Auditorium eager to engage and listen, and the title—a conversation—could not have been more fitting.

Kanter is a Swiss-born, Turkish professional basketball player who joined the Celtics this year. At the age of 17, he moved to the United States to play basketball. He attended prep school before being recruited to the University of Kentucky. Due to different amateur rules in Turkey and the U.S., Kanter was allowed to assistant coach but not formally play with the Wildcats. He declared himself eligible for the NBA draft in 2011 and was selected as the third overall pick by the Utah Jazz. He played for the Jazz until 2015, and since then he has played with the Oklahoma City Thunder, New York Knicks, and Portland Trailblazers before arriving in Boston.

Kanter’s professional sports career has given him an acknowledged amplified platform to engage in public service and advocacy, both of which are important to him. The issues he focuses on are education, freedom of speech, due process, and religious rights, in Turkey and around the globe.

Swidey asked Kanter about his decision to come to the U.S. to play basketball, and about his first impressions of the country.

Kanter responded, “I feel really blessed in America because we have freedom, we have democracy here, we have human rights, we have people respecting each other. Sadly, we don’t have that in my country, in Turkey.”

He added, “One of the biggest reasons I came to America was because in Turkey, you cannot go to school and play basketball at the same time. You have to pick one—either education or sports. So, I wanted to do both. I wanted to go to college and get my education and play basketball at the same time.” Kanter spent his early education in Hizmet (service) schools. Kanter described that experience as a place where “it doesn’t matter what your background is, what your color is, your religion, your culture. What I learned was leave your differences on the table and try to find out what you have in common.”

Swidey asked Kanter how he balances basketball and activism. Kanter said that it was tough, that while some players may feel like they should not engage in activism, he feels like he has to speak out when he sees something wrong. The spark for him was when Turkey started to close schools. It all started with a tweet. He said, “I don’t care what you’re up to, but you cannot fight against education. Once they started closing down schools and dormitories and universities, I [felt] like I had to say something about it. Just because I had this platform, when I say something it became a conversation, especially in Turkey.”

The last time Kanter was in Turkey, in 2015, he said he had a conversation with his family. “Look, there are some things that are going to happen in our country, and because I’m talking about them you might be affected. My father said, ‘If you’re on the right path, we’ve got your back.’” The last day of his visit, he remembers seeing his mom and his sister standing and waving on the balcony and thinking this is the last time he would see his mom. Kanter said he knew it was going to heat up, knew that the Turkish government was not going to stop.

Shortly after his trip, Turkey revoked his passport, stranding him in Europe until the NBA worked with the U.S. to get him a green card. His father, a genetics professor, was fired from his job, his youngest brother was kicked off of basketball teams, and his sister, who graduated from medical school, could not get a job. His mother subsequently released a public statement disowning him. Kanter has not had contact with his family in Turkey since then, though he does maintain contact with his brother who plays basketball in Spain.

Despite these hardships, Kanter insists that using his platform is important to continue his political activism and charitable pursuits to help those that are less fortunate than him. At one point in the conversation, Kanter gestured to the crowd of Tufts’ students and stated his belief in the younger generation.

Kanter’s philosophy also aligns with his basketball teams’ ambitions to leave their differences—in religion, culture, nationality—in the locker room. He explained that when they’re on court, they’re a team, and basketball has that uncanny ability to bring them all together. Kanter also said that the Celtics’ coach’s philosophy is about cultivating team chemistry, which promotes a sense of friendship and harmony in the team and solidifying their game on the court.

The Tufts’ Women’s Basketball team, coming off its first undefeated regular season, was in the audience, and Swidey asked Kanter about an article he recently had written for TIME Magazine on pay equity and women’s basketball. Kanter said he wrote the article because “they don’t get the same attention that they deserve.” He mentioned the attention the NBA stars get and then noted that people do not mention that WNBA player Skylar Diggins-Smith played the whole season while she was pregnant. He said the inequity had been bothering him for eight or nine years.

In 2016, Kanter started his own foundation, The Enes Kanter Foundation, to foster awareness and help children's development through education, poverty alleviation, and social harmony across the globe.

The conversation was co-sponsored by the Tisch College for Civic Life.

You can watch the conversation with Kanter here.