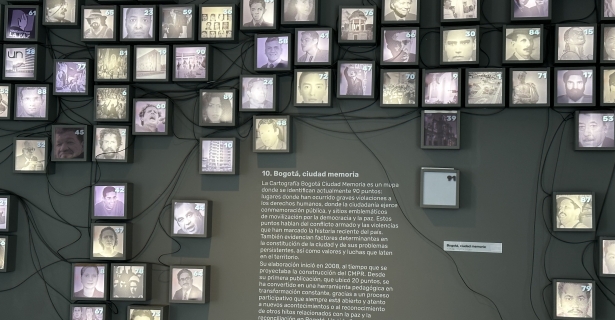

On May 14th, the group representing LAC (Latin American Committee) left Boston to land in Colombia in the afternoon. The different research topics that my peers and I had, embarked us on a journey of 12 days through Bogotá and Medellin. My research proposal was focused on the 2022 Elections in Colombia, which caused a shift from a right-wing government to a left-wing one. It especially touches upon the legacy of the Armed Conflict in Colombia and the way it played a role in the elections and peace building and reconciliation efforts undertaken by the current government. During my stay in Colombia, I got the opportunity to interview professors at the Universidad del Rosario (Bogotá) and EAFIT (Medellín), people at Witness For Peace Colombia and the Centro de Memoria, Paz y Renconciliación, among others people and attend different events in the areas, which allow me to gain multiple perspectives and insights for my research topic. The different museums and events that I visited, which included Museo Casa de la Memoria in Medellín and Centro de Memoria, Paz y Reconciliación made me gain a deep perspective into how the population lived the Armed Conflict, the disappearance of people due to forced recruitment by armed groups or for retaliation and reprisals. The museum located in Medellin recalls three stories of people who went missing during the time of the armed conflict and the work performed by Madres de la Candelaria, which is an organization formed by mothers in Colombia whose sons were victims of extrajudicial killings. The organization raises awareness about these crimes, advocates for justice, supports affected families, and calls for accountability. The first story talks about a kid and how armed groups at the time kidnapped multiple kids in order to make them soldiers in the future. The kid refused to follow orders and was killed and thrown in the river by armed groups. The second story was about a mother, her son, and her daughter-in-law. The son and daughter-in-law went missing because they participated in activities against the armed groups, and the son saw the military performing an action they should not have done, and he knew they would not leave him alone until he disappeared. The last story is about a child that was taken away from their parents through child trafficking to be illegal adopted by another family. The stories presented in the museum serve as a reflection and memorial place to understand the profoundly mark left in the Colombian population. In the Centro de Memoria, Paz y Reconciliación (CMPR) located in Bogotá, they had different expositions surrounding peace and peace actions in the country. One of my favorite parts about the center was a mural where people are constantly writing about their thoughts and feelings related to resistance and why they resist for, throughout the mural some of the answers that sparked my attention were about how corruption silences their town and they do not want that anymore, for liberty, to not be indifference, to remember the history and to not be condemned to repeat it, and for the ones that do not have a voice anymore. The Colombia population wants peace, transparency, and justice for the ones that are missing. In the outside of the center, there are letters from families who relatives were killed or kidnapped by the National Army. The letters are few of the thousands of stories of families who experienced the same. During my days in Bogotá, I spoke with a member of the CMPR. The person —part of the staff of CMPR— explained to me how the center serves as meeting place for people around the subjects of peace, memory, and reconciliation. The center listen to the needs and demands of people regarding the subjects previously mentioned. Part of those needs and demands include more support from the state, public dialogues, and increase relationship with schools. Their work with schools is about converting the subjects related to peace, memory, and reconciliation to be more accesible for children and accompany the schools of Bogotá in the implementation of memory actions. During my conversations with professors of EAFIT and Universidad del Rosario, and staff from Witness For Peace Colombia I was able to understand more profoundly about the change of government in Colombia. The message across different interviews was clear, people wanted a change. This is especially important in populations such as Afro-Colombians and Indigenous people that were tired of not being represented in the government. Moreover, an insight that I got for Witness For Peace Colombia was that people voted for a change maybe not for them, but for their future generations. In that way, their descendants will get the chance their never had and live in a Colombia that is different, a Colombia that is transparent and were all people’s voices are heard. Furthermore, another relevant aspect was how Petro’s victory was significant since in his other attempts for the presidency he did not start communication with right-wing groups. During this election, Petro also gain the vote of people who would typically vote for right-wing parties/candidates. Finally, that the message of “Paz Total” (Total Peace) can be received by skepticism since achieving peace completely –totally— will be hard to achieve or even almost impossible since Petro’s government has already faced challenges in their negotiations with guerrilla groups.