This summer, I am lucky to be interning with the International Indigenous Rights NGO, Cultural Survival. I have mainly been working on communications and on a project called Indigenous Rights Radio, which sources and creates radio programs to be distributed to Indigenous community radio stations. The aim of this program is to share knowledge and experiences in the pursuit of decolonization, and to keep Indigenous communities informed to be able to defend their own rights and cultures. Radio and community media are essential formats for distributing information in many Indigenous communities that do not have access to the internet or phone service, as most people are able to afford a radio receiver.

For my first task, my supervisor asked me to find someone to interview to create a program for Pride Month. Not so difficult, I originally thought. I sent out emails to indigenous LGBTQ+ activists, artists, academics, musicians, educators, and more, asking if they would be interested in talking with me about decolonizing gender and sexuality. Over the next week, I received replies from two people: a young environmental activist from the Xakriabá people of central Brazil, and an ecologist, teacher and environmental drag artist from the Munduruku people of the Amazon.

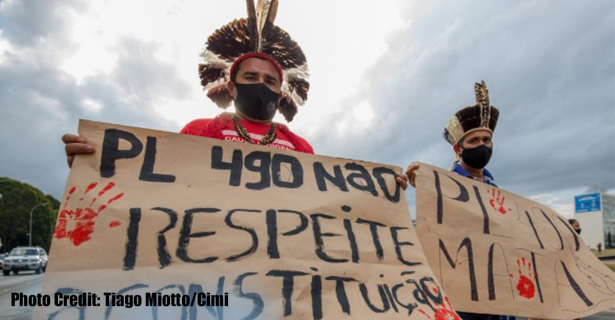

The young environmental activist was currently protesting in the capital. First proposed in 2007, the Brazilian Congress was debating passing Bill PL 490, which would strip the indigenous land rights of many Indigenous groups in Brazil. Specifically, it would create a temporal “cut-off” point, so that Indigenous groups could have their land rights revoked if they could not prove that they inhabited that land when the current Brazilian constitution was passed in 1988. Not only is it difficult to prove inhabitation at any time, but there were still many indigenous groups in Brazil who had not had contact with any governmental body in the 80s who could produce official records.

The environmental drag artist also was not immediately available to be interviewed. He did not reply for a week, so I sent another message. He apologized and said that he was now out of the city in his family’s village and would not be able to call until he was back in the city with WIFI. I told him not to worry and that we could call in a couple of weeks.

At this point, I contacted my supervisor. I told him that I did not think I was going to be able to get an interview done before the end of Pride Month. We were both well aware that Cultural Survival creates these radio programs specifically because of the technical issues that so many Indigenous communities face in accessing WIFI, and that we must be flexible. The organization as a whole had also been tracking PL 490 in Brazil and understood the gravity of the situation.

The next day, the news came out that PL 490 had passed. My heart dropped, knowing the destruction that was going to ensue. However, I did not expect it to be so fast: later that evening, I was scrolling through Instagram, when I saw a post from the young environmental activist that I was hoping to interview. It was a video of the school in her village, which had been subject to an arson attack. It was ablaze, and it was clear that the building was about to collapse. In her caption she wrote of the heartbreak, of the violence she had suffered whilst protesting in Brasilia, and the loss of the school to her community.

I realized I needed to take a step back. As my supervisor wanted to explore and share the important topics of decolonizing gender and sexuality, and I wanted the chance to use my Portuguese language skills, I had quite missed the point here. Cultural Survival works to empower Indigenous People around the world. Instead of asking these activists what we could do in their moment of need, I asked them for a favor, because it happened to be western culture’s Pride Month. Instead of rushing through our calendar of themed months, empowering international journalism requires far more compassion, flexibility, meaningful relationship building and massing the mic to allow those we intend to help to speak for themselves. I am learning over this summer that is what Cultural Survival, as an indigenous-led organization, does. However, it seems that it will take me some more time to decolonize my own approach to international journalism.