Written by Jeremy Zelinger, IGL staff member

Eight miles south of the Syrian border, in the middle of the Jordanian desert, more than 100,000 Syrian refugees live in makeshift homes and tents within three-square-miles. This is the Zataari refugee camp. A year ago it was home to about 100 families. Today it is the fourth largest city in Jordan.

Life in Zaatari is difficult. The camp’s inhabitants face a range of physical and psychological challenges. They have limited access to clean water, nutritious food, or healthcare. They face the emotional strain of displacement and family separation. And because Jordanian law forbids refugees from working, the population of Zaatari is helpless in providing for itself. Instead, the camp’s authorities –the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the Jordanian government – offer services in partnership with non-government organizations.

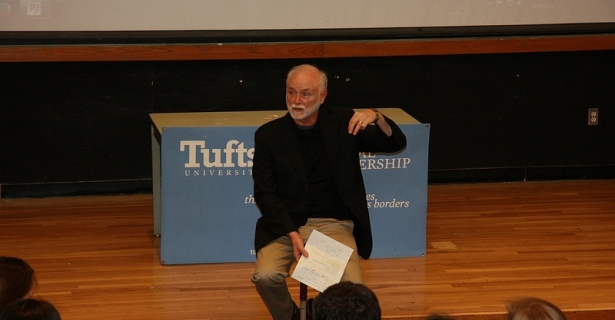

Quest Scope is one such organization. Its founder and president, Dr. Curt Rhodes, spoke to the EPIIC class in October. He was accompanied by Quest Scope’s emergency response coordinator, Mike Niconchuk, an IGL alum.

“We create space to develop Syrian agency.” Rhodes said. “This is the way it has to be done. People have to be actively involved in improving their circumstances and improving the circumstances of others.” When Quest Scope’s staff decided to create a database of children in Zaatari, Rhodes explained as an example, they found a Syrian refugee with technical expertise to design it. The refugee was able to collect data from within the camp that outside organizations could never access.

“[Agency] gives you a reason to get up in the morning. It also gives you a reason not to blow yourself up and to blow others up. It gives you hope. It takes away fear,” Rhodes said.

Rhodes first moved to the Middle East in 1981, amid the civil war in Lebanon. He took a teaching position at the American University of Beirut, but the university closed as the war escalated. To keep himself busy, Rhodes worked as a triage officer for injured Palestinians. Many of his patients were massacred at Sabra and Shatila.

“CNN’s cameras panned over the bodies lying in the streets of Sabra and Shalita and I knew their names. I had cared for them, delivered their babies. I was absolutely astonished that people could be erased so easily as if they had never been,” Rhodes said. Quest Scope’s motto – ‘putting the last, first’ – comes from Rhode’s experience with the Sabra and Shatila massacre. He founded the organization in 1988 to empower marginalized communities in the Middle East, like the Palestinians who had been erased. Quest Scope now runs programs in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Northern Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Mauritania and Sundan. Since 2002 it has impacted over 200,000 people. But as the civil-war in Syria rages on and refugees continue pouring out of that country, Quest Scope is focusing its efforts in places like Zaatari.

Mike Niconchuk, Quest Scope’s emergency response coordinator, spends the majority of his time directly engaged with the refugees of Zaatari. A Tufts alum, Niconchuk was co-president of the IGL’s Oslo Scholars program, which links Tufts undergraduates to conferences, internships, and research opportunities related to human rights. In 2011, Niconchuk attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland where he met Dr. Rhodes and later agreed to join the Quest Scope team. He now lives in Jordan.

“A lot of the degradation of individuals’ mental health comes after their exposure to trauma in a conflict, particularly in a refugee situation, and it comes mainly via social isolation.” Niconchuk told the class. “The idea of having your network of support taken away from you – you are who you are because of your family and friends – when that disintegrates, you begin to feel very unsafe.” Niconchuk described the enormous challenge of trying to help the refugees in the camp. “The definition of ‘life saving’ is expanded in an emergency context when you don’t have education, mental health, sanitation - there is a reason why they call it ‘complex humanitarian situations.’ ”

Zaatari’s complexity has inspired several EPIIC and NIMEP students to propose research trips to study refugees in Jordan. Umar Shareef, a freshman in EPIIC, will study the role of spirituality in Zaatari. Safiya Subegdjo, a sophmore also in EPIIC, plans to assess health services for refugees in Jordan. Ayesha Forbes, a junior in EPIIC, will study economic entrepreneurship among female refugees. Leah Muskin-Peirret, the student president of NIMEP, is planning to study gender-based violence in Zaatari. Hannah Freedman, also of NIMEP, will analyze the implications of Jordan’s rising refugee population for regional water-negotiations. Elizabeth Robinson, who is in both EPIIC and NIMEP, will study Zaatari’s informal economy.

These students will work with Quest Scope in Jordan. They will learn from Rhodes and Niconchuk. Like Quest Scope, they will attempt to shed light on the marginalized refugees of Zaatari. They will put the last, first.