How do our conceptions of space, boundaries, and political borders impact the way we address migration? What is the shadow cast by the partition of India 1947 and how is this related to our perceptions of space? Finally, what can we learn from the history of India’s partition in regard to the practice of conflict negotiation and resolution?

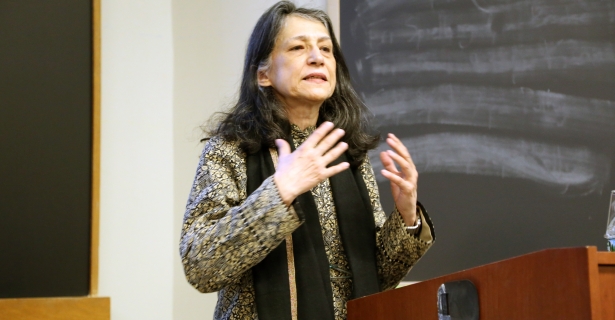

Dr. Ayesha Jalal, the Mary Richardson Professor of History and Director of the Center for South Asian and Indian Ocean Studies at Tufts University, gave an eye-opening talk addressing these questions as a part of the Institute for Global Leadership Student Speaker Series on Migration. She was invited by Tufts International Development: India due to her impressive research and expertise in the region.

Dr. Jalal’s talk addressed the legacy of the partition of India, the creation of Pakistan, and the connections between these histories and the broad ways we perceive migration as a whole. In 1947, India, at the time a British colony, was partitioned by colonial forces into two separate dominions, now India and Pakistan. The partition line was drawn rather arbitrarily, argued Dr. Jalal, and this event not only lead to the mass migration of 17 million across both frontiers at the time, but it has also set the stage for the stability and political climate of the region to this day.

Dr. Jalal stated that, while on paper it seems as if the Partition was a single event, we need to understand partition as an ongoing process which to this day has shaped the South Asian experience. “Partition is a way of seeing and perceiving”, said Dr. Jalal, but British colonial forces saw it as a one-time event, they believed it would be easier to draw lines than to make political accommodations. But, Partition is not just about drawing lines, it is both a way of perceiving space and a method of exclusion. To this day, the Indian subcontinent has been greatly affected by the partition – it has led to interstate tension as well as simmering conflicts, like in Kashmir.

Partition, argued Dr. Jalal, is a callous way of conflict negotiation. She said, we need to rethink the way we perceive space, boundaries, and borders if we ever want to find a model of conflict management that is not only humanistic in nature, but also leads to long term peace. Dr. Jalal challenged the current generation to rethink the way space is perceived: why is it that one line drawn so many years ago has led to so much tension, and how can we rid ourselves of this narrow perception of our environments?

TID: India thanks Dr. Jalal for taking the time to give such a fascinating talk, as well as the IGL for organizing this series and for its continued support for TID.